The Government has now found a policy on the Brexit negotiations. It unearthed it, apparently, in the cool, panelled rooms of Chequers last night. The instant wisdom is that it is a victory for the “pragmatists”.

In British – in particular, English – public culture, anyone claiming to be a pragmatist tends to win the advantage. A pragmatist is supposed to be an open-minded person who sees the facts as they are. The opposite of a pragmatist is an “ideologue” and/or a “fanatic”. Who, outside the wilder reaches of Isil or Momentum, wants to be one of them?

In recent weeks, Remainer activists have skilfully grabbed the pragmatic label. Leavers are presented as the raving ideologues. Trying to avoid cheap jibes about how poor, wild-eyed Tony Blair, noisy Anna Soubry and preposterous Lord Hailsham seem strikingly unpragmatic, I would like to investigate what this supposed pragmatism really is.

It goes wider than the Brexit issue. Essentially, it is the default position of those who have power in this country. In the 1970s, pragmatists coalesced round the idea that Britain must have a prices-and-incomes policy and a tripartite structure of government, business and unions to prevent inflation and economic collapse. This was espoused, with fanatical moderation, by the then Prime Minister, Ted Heath. People who opposed this view were dismissed as crazy “monetarists” on the one hand, or union “wreckers” on the other. The pragmatists prevailed. We duly had rampant inflation and came close to economic collapse.

At the end of the 1980s, having had a thin time under Margaret Thatcher, pragmatic forces at last got back together and insisted that Britain must join the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) of the European Monetary System. By semi-fixing our exchange rate with that of other European currencies, they said, we could impose the financial and economic disciplines we seemed not to be able to manage for ourselves. We joined. The pragmatists’ policy forced extreme rigidity upon our economy. After less than two years of punitive interest rates, and consequent austerity and business closures, the pound came tumbling out of the ERM on September 16 1992, and stayed out. Britain’s economic recovery began the next day and lasted until Gordon Brown’s premiership 15 years later.

In 2016, the pragmatists were unprepared for the EU referendum. They resented the very idea that voters should decide an issue that they considered far too complicated for them. Since they assumed that voters must dislike the EU only out of ignorance, their sole tactic was to frighten them about what they might lose. Despite (because of?) their disproportionate power in politics, big business, central banks, Whitehall and academia, they failed.

Two years on, they are trying essentially the same thing. You cannot blame a company such as Airbus or Jaguar Land Rover for asking the Government what on earth it is doing. All of us want to know that.

But all such companies’ claims about what they might lose from a “disorderly” Brexit assume no possible gains. They do not factor in the exchange rate. They equate a short-term problem with long-term disaster. They concentrate on (and exaggerate) what we might lose in exports to the EU, which make up 12 per cent of our GDP, rather than the opportunities our greater freedom might gain for the other 88 per cent. They equate comfortable arrangements they have made for themselves in Brussels with the general good. They present their fears for their own comforts as things that should frighten the rest of us. This is not impartial calculation, but vested interest getting all hot and bothered under its vest.

A true pragmatist thinks hard about the reality behind appearances. The Remainer pragmatists do not. They like the status quo. They do not try to imagine why so many of the rest of us don’t. In this sense, although they are full of information, they are impervious to the facts, which is a most unpragmatic state of mind.

They are also, did they but know it, in thrall to a powerful ideology. It goes back to Plato. It holds that rightly guided, educated people – “people like us”, as our pragmatists might put it – must run things. Its modern form is bureaucracy in the literal meaning of that word – power held by the bureau, rather than the elected representatives of the people.

National solidarity and representative democracy are based on the idea that all citizens have an equal right to choose their rulers. If they live under a system, such as the EU, which frustrates that right, they become profoundly alienated. People trying to reverse the referendum result, or empty it of meaning, may think they are applying common sense, but they are enforcing this anti-democratic bureaucratic ideology and increasing that alienation. If you do not understand why that matters, you are as unpragmatic as the ancien régime before the French Revolution, and may suffer the same fate. In the meantime, as the constituencies are starting to tell MPs, you lose the next election.

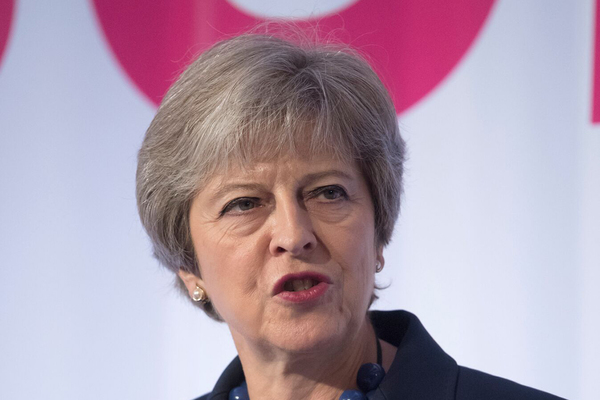

As the scene moves back to talks with Brussels, we shall all be reminded that the least pragmatic players in this whole, long story are the people with whom our pragmatists keep telling us to make a deal – the EU Commission. Two years of arguing with her own colleagues have brought Mrs May no closer to grappling with this, the most dogmatic body in the Western world.

No British pragmatist has even tried to explain why the pre-emptive cringes advocated, incredibly, as our opening bid in the trade talks will induce Michel Barnier to make the deal with Britain that has so far eluded us. Why should he be impressed by the “common rule book for all goods” that Mrs May seeks? He already has one: it is called the customs union. If he thinks she is weak, he will beat her down yet further. She has admitted in advance that her latest plan makes it impossible for post-Brexit Britain to make a trade deal with the US: that’s a funny triumph for pragmatism.

The true pragmatist’s approach to these negotiations should be based on an estimate of power. If they are structured – as Mrs May seeks – to obtain special favours for Britain, they will fail, because the power of favour rests with the Commission. What have we done to make it help us? If, on the other hand, Britain says it is leaving anyway, in letter and spirit, because that is what the referendum decided, then it cannot be stopped. Faced with that reality, the EU and Commission are forced to consider how to make the best of this – for them – bad job.

Compare the high Commission rhetoric about the inviolable sanctity of the open border with Northern Ireland with the new war of words about closing borders between Germany, Austria and Italy – contrary to the EU’s own Schengen rules – because of the migration crisis. The former is a goody-goody game; the latter is serious. Theoretical talk is quickly crowded out when reality becomes unavoidable.

In all this time, Mrs May has never got serious in our power battle with the EU. She shrinks from it. So she is gradually, pragmatically, losing.

Follow Charles Moore on twitter @CharlesHMoore; read more at telegraph.co.uk/opinion